How did Montmartre become the destination for café-concerts? How did it influence Rodolphe Salis to make a cabaret? What makes Le Chat Noir cabaret unique? We have to go back first.

Haussmanization and the Cabaret

Between 1853 and 1870 George-Eugene Haussman ran massive public works projects. Enormous boulevards cut through the medieval streets. New sewers were built. Suburbs are annexed into the city.

This process completely reshaped the city.

Without going into too much detail, some bourgeoisie Parisians embraced the sweeping modernity.

Haussmanization pushed the working classes and artistic community to the periphery of Paris. Maybe I’m simplifying here, but it sounds like your standard gentrification.

Amid war, revolt, and modernization, Montmartre was annexed into Paris. Montmartre’s fields, village-like dwellings, and iconic windmills.

Montmartre gave the impression of a quaint village but nightlife boomed. Cheap lodgings, food, and bookshops attracted bohemians pushed out of the city. Painters and public entertainers moved to Montmartre and the cabarets soon popped up. Shadowy streets teemed with prowling artists, sex workers, the dispossessed, and other “outsiders”.

Montmartre’s Café-Concerts

Montmartre formed a unique identity separate from the greater Paris. Inhabitants thumbed their noses at bourgeoisie sensibilities. They spent their nights at raucous café-concerts. These were hole-in-the-wall places with cheap seedy entertainment. (And they sound fabulous.) John Houchin in The Origins of the Cabaret Artistique describes programs held at café-concerts:

“…Second-rate singers wailing sentimental or patriotic songs in smoke-filled cellars, with only a small platform for a stage and an ill-tuned piano providing accompaniment.”

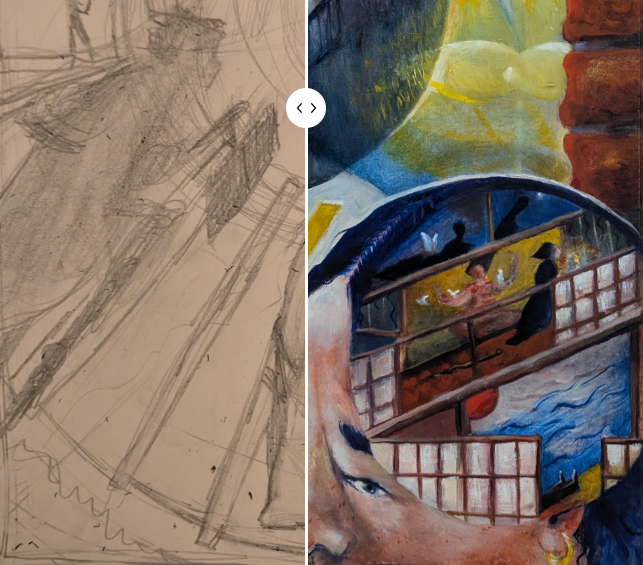

Artists painted vivacious entertainment. One of these characters was the chanteuse, Eugénie Emma Valladon, known as Thérésa. An extravagant and talented performer featured in many paintings.

The singer holds her hands like a dog. She’s shown as a bit rough around the edges. The painting is gorgeous and lively. A sea of people turns into a background blur.

Thérésa is a fascinating figure worth reading about. Imagine her as a precursor to such stars as Edith Piaf. Thérésa would say: “I am a girl of the people, I love the people and I am amusing them, so I find a way not to part with my family.” She embraced her “low” birth. And Montmartre’s workers, housemaids, unknown artists and writers loved her for it.

As the café-concerts grew in popularity more and more of them sprouted up in Montmartre. Le Chat Noir started as one of these cafés. But it ended up as the first true artistic cabaret. It was the first to combine bawdy songs, modernist experiments, journals, poetry, and parody. Artists ran, decorated, and marketed the joint in creative and ludicrous ways.

Enter Le Chat Noir Cabaret – Beginnings

In 1881 Salis established the small Chat Noir at 84, Boulevard Rochechouart at the site of an abandoned post office. Supposedly Salis named his cabaret after the folklore character of a mischievous black cat. The cat sometimes punished disobedient children. Other times he embodied the role of a lover. Its naughty nature fit the cabaret perfectly.

Another famous cabaret singer, Yvette Guilbert, told of a different origin story: “A black cat, an old tomcat was found in the shop. He gave his name to the cabaret that was installed there. He was the mascot.”

Either way, the cat also became a symbol of artistic freedom for the the Chat Noir cabaret. A cult developed around the slinky black cat. New ballads, art, and comics praised the feline and the uninhibited nature associated with it.

In one of Adolphe Willette’s drawings for the journal Le Chat Noir features the black cat. He sinks his teeth into a nude woman.

She’s fallen from her chair by the vanity mirror and is writhing on the ground in stockings.

Artists also depicted the cat lounging on a sliver of moon and looking down at the viewer. He’d chase female cats, or even resurrect after death from the jaws of a dog. Salis saw the black cat as a symbol of freedom from societal constraints. Le Chat Noir, its mascot, and all they stood for became a rallying point.

Emerging artists and writers within the cabaret developed close-knit circles. Members influenced and pushed each other toward fame.

Le Chat Noir Closes Shop

Le Chat Noir closed in 1897. A soap boutique replaced it. (Which reads as some attempt at poetic justice.) Salis died a month after the closure.

Alphonse Allais, editor-in-chief of Le Chat Noir for a time, mourned the closure of the cabaret. He captures the response of patrons and would-be patrons (like Pablo Picasso):

“The Chat Noir is dead. The cabaret is closed! The Shadow Theater has vanished. The poets and chansonniers have dispersed! The journal is abolished!”

Ironically, the cabaret and its competitors changed Montmartre from a seedy neighbourhood into the hot new destination.

The Chat Noir muddled the waters of culture, entertainment, and class. It bucked up against even the Academy. Patrons blurred class lines in smoky cabarets. Other imitating cabarets sprouted out across Montmartre and Montparnasse. Artists linked to Le Chat Noir, such as Willette, went on to other projects. He designed the Moulin Rouge mock-up windmill.

Maurice Donnay, the French dramatist, stated

“The Chat Noir! I don’t have pretentions to cover a subject so vast…But to define the ‘spirit of the Chat Noir’, that is easy…its purpose was to spread enjoyment to all men through all of life’s situations.”

And so it did.

Next Post: Experiments, Spectacles, and Parody at Le Chat Noir

Appignanesi, Lisa. The Cabaret. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004.

Chapin, Weaver. “High Ground, Low Life.” The Wilson Quarterly, Vol. 29, No. 3 (Summer, 2005): 111-113.

Fields, Armond. Le Chat Noir. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1993.

Gendron, Bernard. Between Montmartre and the Mudd Club: Popular Music and the Avant-Garde. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

Houchin, John. “The Origins of the “Cabaret Artistique”.” The Drama Review: TDR Vol. 28, No.1 (Spring, 1984), 5-14.

Maubert, Franck. Toulouse-Lautrec in Paris. New York: Assouline Publishing, 2004.

Phillip Dennis Cate and Mary Shaw, eds. The Spirit of Montmartre: Cabarets, Humor, and the Avant-Garde, 1875-1905. New Jersey: Rutgers, 1996.