The Tale of Genji continues to fascinate audiences one thousand years later. The writing, culture, poetry, and court politics contain enough to sate scholars for their entire career. But today, I’m going to look at something specific, the compositional techniques, projections, and angles used in the art in The Tale of Genji and other medieval Japanese scrolls and screens.

The Tale of Genji, Briefly

Written in the 11th century, The Tale of Genji is often regarded as the first novel. (Buzz off Samuel Richardson, I’m still annoyed by all 1,500 pages of Clarissa.) While there is still some debate, most scholars recognize Murasaki Shikibu as the author, a lady-in-waiting. The book follows the escapades of the beautiful prince Genji and his many (many) passionate romances. The masterpiece is filled with life, love, grief, and so full of humanity. It’s no wonder that it continues to influence.

And my personal aside, I’ve been more and more interested in the use of perspectives in art outside of the traditional Western logical linear perspective and all its points. My take: I get, well, bored of western perspective models. Or the way it’s taught in schools at least, with a “realistic” and accurate focus. Other forms of perspective should be explored alongside it. (And I feel the same about frames being the standard. The genius Emma Amos and her incredible work alone prove this. That’s for another day.)

Anyway, there are illustrations showcasing many centuries of love for The Tale of Genji all the way to today with manga. Artistic innovations grew alongside the Genji but one in particular stands out from early on: fukinuki yatai.

Fukinuki Yatai: Roof-Blown Off

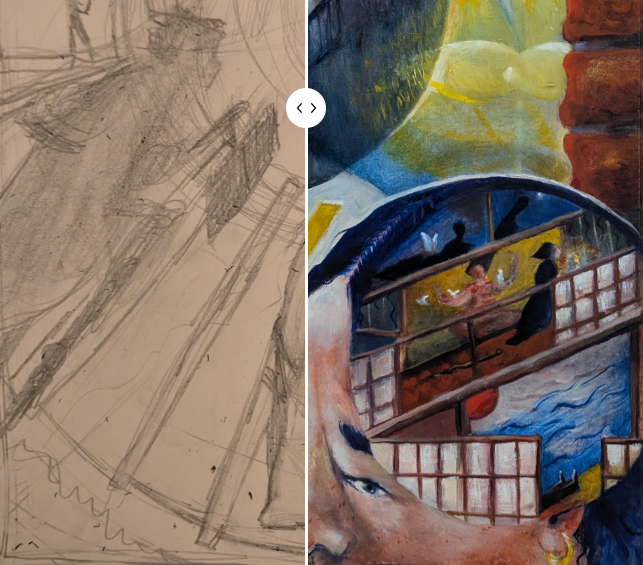

Fukinuki yatai (吹抜屋台), or “roof blown off”, give these early pieces a unique feel. Essentially when using this compositional technique the roof dissapears. Sometimes select walls also dissapear. So we, the observer, can omnisciently view entire interior and exterior scenes without obstruction.

Rooms and exposed timber frame compartmentalize scenes. Two, or more, scenes can be shown at once and can play off of each other. And you can see this as far back as the 12th century.

Isometric angle: Roughly 50°

For example, check out the frantic ladies-in-waiting and saturated colors on the left juxtaposed to the calm figure, Kaoru, on the right. Movement and colors heighten the contrast between the two scenes. Kaoru remains patiently unaware of the hustle and bustle of the women as he waits to be invited in. But only fukinuki yatai makes this possible.

Observing these intimate interior scenes as an observer from up on high feels like stepping into the writers shoes. The roof blown off serves as an implied broken fourth-wall. It’s an, in my opinion, ingenious compositional way to show interior and exterior scenes simultaneously.

Isometric Projections

Another aspect of this style of art I wanted to highlight is the use of isometric perspective. Technically, it’s isometric projection. That is, projection of a 3D space onto a 2D plane.

Take a look at this image showing different projections, particularly an isometric projection and perspective projection.

The lines that make up the plans used in isometric projections are parallel, not converging to a point like in linear perspective.

Architects and engineers frequently use this projection. Isometric projections mean viewers can see an entire scene and it’s elements equally. The artist doesn’t need to obfuscate and minimize elements or worry about where the viewer is located.

But, it’s not as used in traditional Western art, though I have seen it seen it in illustrations and frequently in top-down video games. (But I didn’t know the name for it.)

David Beynon uses the more accessible terms “2.5 dimensional” and “superflat” in their great article to refer to isometric perspective in architecture.

[…] the isometry of the architectural representation serves to frame, flatten and abstract pictorial space, and so emphasises the continuity between the different compartments of a painting.Beynon, David, Superflat architecture : culture and dimensionality, in Interspaces : Art + Architectural Exchanges from East to West

There is a lot to discuss when it comes to projections, but keep in mind the angle of the faces in isometric projection remain the same. Often it’s 30 degrees.

Is There a Standard Isometric Angle in The Tale of Genji?

Back to the Genji. So we’ve established isometric projections and fukinuki yatai. The crux of this exploration started with me wondering: what angles are used in The Tale of Genji and similarly styled scrolls and screens?

Turns out it depends. A lot. Which seems obvious. Here are a few examples through the centuries. (All measurements are rough.)

Isometric Angle: 25°

Isometric Angle: 30°.

Isometric angle: 40°

Isometric angle: 30°

God, what a beautiful piece. The Met explains the scene:

This single screen, one of the finest examples of painting by Tosa Mitsuyoshi, encapsulates the imagined visual splendor of Genji’s Rokujō estate and conflates episodes from two different days in one composition. Ladies-in-waiting from the autumn quadrant of the Umetsubo Empress (Akikonomu) have arrived in Murasaki’s spring garden on a water bird boat on the upper left. The foreground scene takes place the next day, when page girls spectacularly costumed as paradisal kalavinka birds and butterflies of the court bugaku dance arrive at the autumn quadrant via dragon boat. The girls have been sent by Murasaki with flower offerings for the Empress’s sutra reading. The profusion of cherry blossoms throughout the screen illustrates the dominance of the spring season.

Isometric angle: 28°

Isometric Angle: 168°

Isometric Angle: 20°.

I didn’t see any strong angle trends in this limited range of illustrations from the Genji and other tales in a similar vein. But, this imperfectionist feels like they have a stronger grasp on what isometric projection entails and I’m excited to start using it.

I’m not one for following instructions really but this seemed like an excellent illustrative tutorial.

Read and Watch More:

Beynon, David. Superflat architecture : culture and dimensionality. Interspaces : Art + Architectural Exchanges from East to West, The University of Melbourne, School of Culture and Communication, pp. 1-9. 2012.

Watanabe, Masako. Narrative Framing in the ‘Tale of Genji Scroll’: Interior Space in the Compartmentalized Emaki. Artibus Asiae 58, no. 1/2, pp. 115–45. 1998.

Read The Tale of Genji, obvs