Wander around any art museum in the UK and you’ll likely encounter a Peter Lely portrait of a heavy-lidded beauty languishing in an ornate frame. Light skin and silk set against deep colors. Once you see this Restoration (1660-1714) ideal of perfection, you’ll recognize it again and again.

Why do they look the same? What do these paintings say about beauty standards in Restoration England?

A bit of history first.

Peter Lely was a Dutch painter that came to England in 1643. Once there, he thrived. His talent kept him safe during the tumultuous period of the Interregnum. And his earlier style feels more Anthony Van Dyck than the lush portraits of women he came to be known for in the Restoration.

Take Lely’s Oliver Cromwell portrait (an obligatory fuck you and a Pogues song – RIP Shane).

Cromwell supposedly instructed Lely to paint him “pimples, warts, and everything” (according to the curator at The Cromwell Museum). With retellings, this evolved into the phrase ‘warts and all’. This portrait aims for authenticity over artifice.

After the Interregnum, 1661 Peter Lely was appointed Principal Painter in Ordinary for Charles II. (Basically, Mr. Big Shot portrait painter for the court and aristocrats.)

Charles II’s reign is known for, among other things, debauchery. I mean, years of no booze, festivities, sports, or fun will do that. But it’s also known for creativity. When the Merry Monarch reopened up theaters women finally were allowed to act. Female authors and playwrights created huge bodies of work that still hold up (in my opinion anyway). And, women became famous mistresses of the king and beauties of the court.

Women used these avenues to gain power. Simplifying a bit, but Nell Gwyn is probably the most famous Restoration woman, and one with an incredible rags to riches story. She was a successful comedic actress, and used her beauty, wit, and charm to gain access to power. (Read: sleep with the King.)

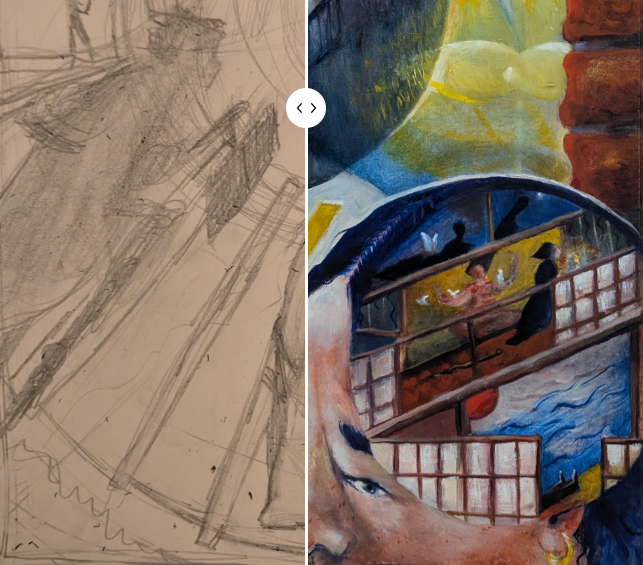

Compare Cromwell’s portrait to this one of Charles II’s famous mistress (likely Gywn herself or perhaps Barbara Villiers).

Sumptuous stuff. The authenticity of the Cromwell portrait gives way to adornment and idealized forms.

Enter the Windsor Beauties. A collection of 10-12 portraits (depending on the source) of ladies from the court of Charles II.

Here’s most of them:

The women are all pale but blushing, dressed in silks exposing their breasts, adorned with jewels, and have elegant hands. But moreover, the faces look strikingly similar.

I overlayed the Peter Lely portraits on top of each other at 30% opacity (flipping the axis when needed). And it honestly made me feel more sane as each layer just fell easily on top of the other – especially the eyes. Even the rounded shoulders and jewels aren’t too far off from being on top of each other.

So why? It could be Lely found a method that worked well for his studio and could finish commissions quickly. No doubt he was a wealthy man during his lifetime. After his death he left supposedly just a mess of canvases. So there’s likely an element there.

But I think there could be more to it, I’m pivoting to one of my least favorite things, social media standards! I don’t think it’s a huge leap to equate these portraits to modern filters, photoshop, facetune, etc.

Affording this type of ‘work’, whether in the form of a portrait, technology, time, or plastic surgery can be a status symbol. I think we see the same thing throughout history, the “beauty standard” that is in many ways, by design, exclusive. Today it might be filters, buccal fat removal, veneers, and whatever else. Who knows what tomorrow’s standard could be. (And, to be clear, not shaming, if it makes people actually feel good, great. What I take issue with is when people feel forced.)

But in 17th century England, it was Lely face. If you had the face you were likely someone of note in English society.

I liked this quote about ‘Instagram face’ today:

Hotness is a class struggle. The beauty of the princess justifies her estate. The symmetry of the wealthy, the sanity of the system.

Grazie Sophia Christie, The Class Politics of Instagram Face

A Catch-22 where beauty equals power, and power equals beauty. Or, at least, what people in power think beauty is. The author goes into much more detail about how these goalposts shift, it’s an interesting read.

The faces of Peter Lely’s portraits echo all these themes of power, beauty, trends, and unattainable standards that we still grapple with today.

Next time you look at a portrait, think beyond the technical skill, and more about what they’re trying to portray through their appearance. What they’re carrying, the expression, and the shape of their face itself. Maybe question why our body features are trends and what does that say about how we view beauty and social structures?

And also just tell yourself you’re beautiful, that usually seems like a good idea. Whatever ‘flaws’ you have likely make you stand out.

Read more:

https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/arts-letters/articles/class-politics-instagram-face

https://artuk.org/discover/artists/lely-peter-16181680

https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/blog/who-was-nell-gwynn